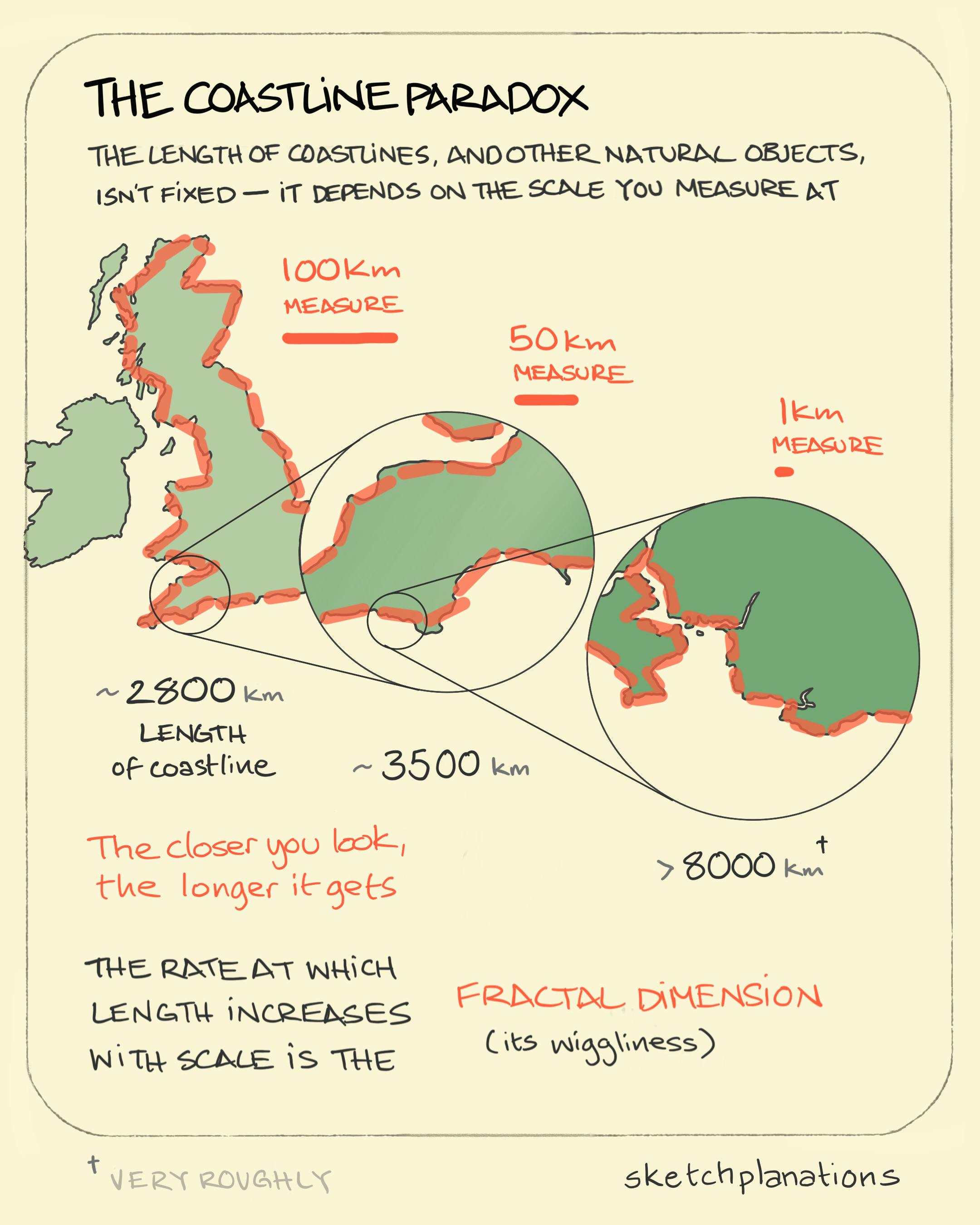

The coastline paradox is the fascinating observation that it’s not straightforward to say how long a coastline is. If you were to measure the coastline of a country by using a ruler on a globe, you would come out with a vastly different number than if you were to pace around the edge. The closer you look, the more wiggles and squiggliness you come across, and instead of converging to a more accurate length, the coastline just keeps getting longer. The smaller your ruler, the longer it gets. This was originally spotted, incredibly, in the 1950s by an Englishman, Lewis Richardson, when trying to check a theory he had that the likelihood of war between countries depended on the length of their shared borders. Remarkably, he found that the quoted lengths of borders varied significantly. While measuring on maps at different scales, he saw that the smaller scale map he used, or the smaller the width of his callipers he measured with, the length systematically increased. When looking at coastlines, instead of borders, some countries had wigglier coasts, and so the length increased at a faster rate with the scale — for instance, Norway’s coastline, with it’s crinkly fjords, increases faster than Britain’s, which in turn increases faster than South Africa’s, as he zoomed in. The rate of this increase later became known as its fractal dimension. Long after Richardson’s research, Benoit Mandelbrot published a paper How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension that discussed how the wiggliness of something like a coastline at one scale can be repeated at smaller and smaller scales. The work led to the later term fractals. Many other things exhibit fractal-like behaviour, such as river networks, borders, brains, frequencies, lightning, and even the stock market. There’s a super section on this in Scale, by Geoffrey West. Also see: The Mercator Projection The difference between Great Britain, the UK and the British Isles…The coastline paradox is the fascinating observation that it’s not straightforward to say how long a coastline is. If you were to measure the coastline of a country by using a ruler on a globe, you would come out with a vastly different number than if you were to pace around the edge. The closer you look, the more wiggles and squiggliness you come across, and instead of converging to a more accurate length, the coastline just keeps getting longer. The smaller your ruler, the longer it gets. This was originally spotted, incredibly, in the 1950s by an Englishman, Lewis Richardson, when trying to check a theory he had that the likelihood of war between countries depended on the length of their shared borders. Remarkably, he found that the quoted lengths of borders varied significantly. While measuring on maps at different scales, he saw that the smaller scale map he used, or the smaller the width of his callipers he measured with, the length systematically increased. When looking at coastlines, instead of borders, some countries had wigglier coasts, and so the length increased at a faster rate with the scale — for instance, Norway’s coastline, with it’s crinkly fjords, increases faster than Britain’s, which in turn increases faster than South Africa’s, as he zoomed in. The rate of this increase later became known as its fractal dimension. Long after Richardson’s research, Benoit Mandelbrot published a paper How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension that discussed how the wiggliness of something like a coastline at one scale can be repeated at smaller and smaller scales. The work led to the later term fractals. Many other things exhibit fractal-like behaviour, such as river networks, borders, brains, frequencies, lightning, and even the stock market. There’s a super section on this in Scale, by Geoffrey West. Also see: The Mercator Projection The difference between Great Britain, the UK and the British IslesWWW…

Read more…