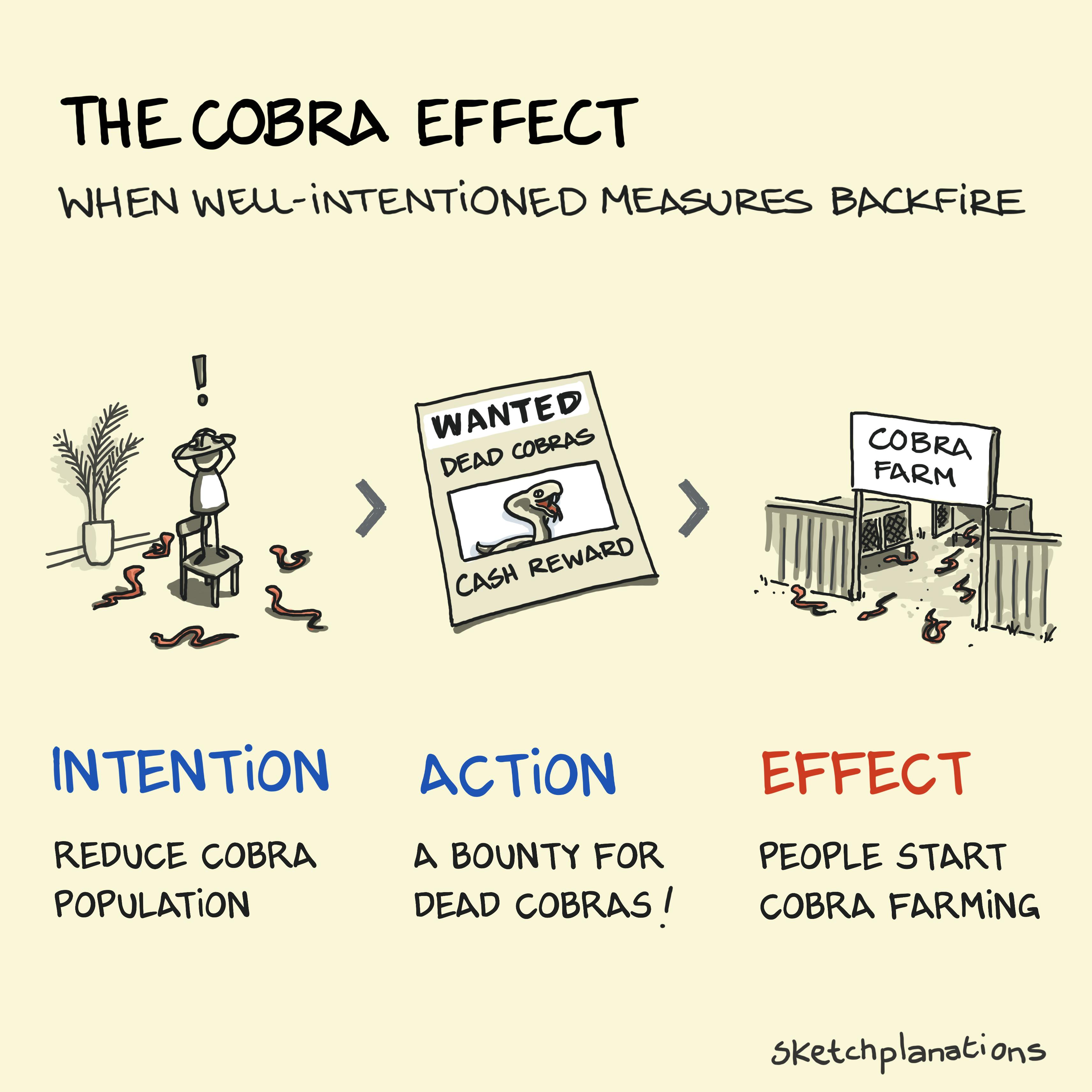

The Cobra Effect

The cobra effect is when well-intentioned actions to achieve an aim backfire and sometimes produce the opposite effect. The story goes something like this: Back in colonial India, the top Brit in charge decided there were too many cobras around Delhi. To reduce the population, they put in place a cash reward, or bounty, for anyone who brought in a dead cobra. The intention was clear. Legend has it that people did bring in the cobras reliably because some enterprising souls had started breeding cobras for the very purpose of getting the bounty. When the authorities realised this, they scrapped the scheme, the cobra farms closed, and the bred cobras were released into the wild, significantly increasing the cobra population by a few orders of magnitude. Hence, the cobra effect: when a well-intentioned measure can have the opposite effect to that desired. It’s not clear how true this story is, but the cobra effect has been demonstrated many times. The Freakonomics podcast on the cobra effect discusses some excellent examples (with references), including: A bounty on rats in French colonial Hanoi, where the bounty was earned by bringing in a rat tail, which went the same way as the cobra story Removing wild pigs at Fort Benning, Georgia, at $40 a pig's tail, that didn’t make a dent. It's possible that the hunters would bait the pigs with all sorts of tempting scraps. Many pigs learned to avoid the hunters and instead bred like crazy while well-fed on scraps. The capital of Colombia, Bogotá, tried to reduce traffic congestion by restricting each car from driving on one day during the week. The result: people started buying more than one car and drove more on weekends. The publication of proposed areas for habitat protection to be protected for endangered species led land developers to respond by building in those areas before the land was protected. People are smart. Incentives work—in the sense that you tend to get what you incentivise. So be careful what you are incentivising. As Charlie Munger said, "Show me the incentive, and I'll show you the outcome." Related Ideas to the Cobra Effect Also see: The law of unintended consequences Goodhart’s Law Campbell's Law What gets measured gets better You get what you measure I tidied up this sketch from the original…The cobra effect is when well-intentioned actions to achieve an aim backfire and sometimes produce the opposite effect. The story goes something like this: Back in colonial India, the top Brit in charge decided there were too many cobras around Delhi. To reduce the population, they put in place a cash reward, or bounty, for anyone who brought in a dead cobra. The intention was clear. Legend has it that people did bring in the cobras reliably because some enterprising souls had started breeding cobras for the very purpose of getting the bounty. When the authorities realised this, they scrapped the scheme, the cobra farms closed, and the bred cobras were released into the wild, significantly increasing the cobra population by a few orders of magnitude. Hence, the cobra effect: when a well-intentioned measure can have the opposite effect to that desired. It’s not clear how true this story is, but the cobra effect has been demonstrated many times. The Freakonomics podcast on the cobra effect discusses some excellent examples (with references), including: A bounty on rats in French colonial Hanoi, where the bounty was earned by bringing in a rat tail, which went the same way as the cobra story Removing wild pigs at Fort Benning, Georgia, at $40 a pig's tail, that didn’t make a dent. It's possible that the hunters would bait the pigs with all sorts of tempting scraps. Many pigs learned to avoid the hunters and instead bred like crazy while well-fed on scraps. The capital of Colombia, Bogotá, tried to reduce traffic congestion by restricting each car from driving on one day during the week. The result: people started buying more than one car and drove more on weekends. The publication of proposed areas for habitat protection to be protected for endangered species led land developers to respond by building in those areas before the land was protected. People are smart. Incentives work—in the sense that you tend to get what you incentivise. So be careful what you are incentivising. As Charlie Munger said, "Show me the incentive, and I'll show you the outcome." Related Ideas to the Cobra Effect Also see: The law of unintended consequences Goodhart’s Law Campbell's Law What gets measured gets better You get what you measure I tidied up this sketch from the originalWWW…

Read more…