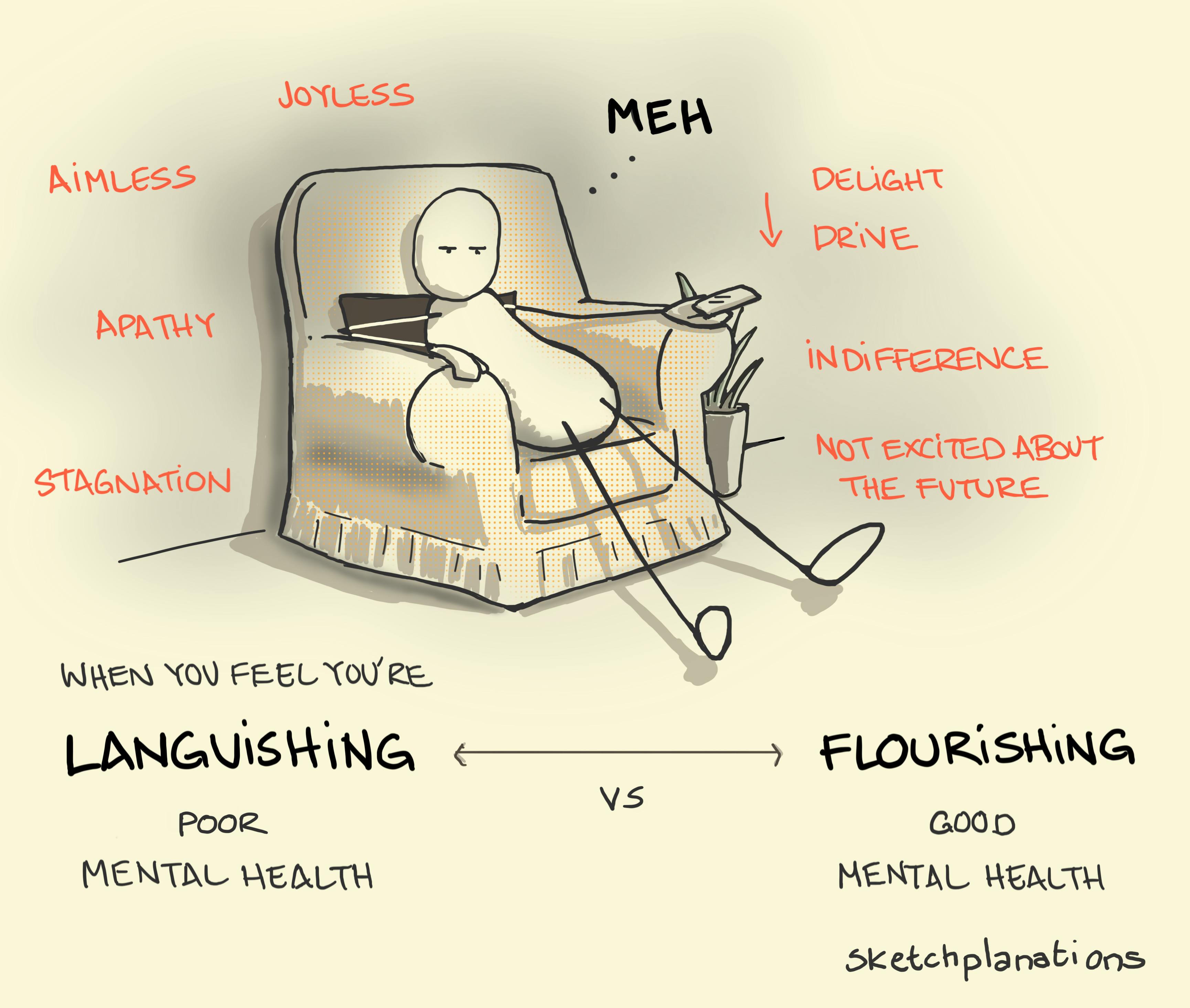

Languishing

Meh. Blah. Can't be bothered? Not excited about the future? Perhaps you're languishing. Adam Grant's NYT article, There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing, resonated with so many people as the coronavirus pandemic drew on. While not having a mental illness or being clinically depressed, many of us associated with a general stagnation or apathy towards things — an absence of, or poor, mental health. Languishing is a counterpoint to how we might feel in prime mental health, full of wellbeing or Flourishing. While languishing may not be necessarily dangerous in itself, if you're languishing you may be at higher risk of mental illness. Some steps Adam suggests we can take: Naming our state can be a first step to doing something about it Looking for small wins that show us progress Asking how our friends and family are doing — having the opportunity to speak to someone about it You also might consider working on the 5 Ways to Wellbeing, getting in some forest bathing, walking a labyrinth, aiming for some flow, noticing when you're happy, or seeing what might bring you hope. — The term languishing for that part of the mental health continuum is from Corey Keyes. See for example, Corey L. M. Keyes. “The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life.”Journal of Health and Social Behavior, vol. 43, no. 2, 2002, pp. 207–222. Armchair and inspiration, as usual, from Bill Watterson. Order a print…Meh. Blah. Can't be bothered? Not excited about the future? Perhaps you're languishing. Adam Grant's NYT article, There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling: It’s Called Languishing, resonated with so many people as the coronavirus pandemic drew on. While not having a mental illness or being clinically depressed, many of us associated with a general stagnation or apathy towards things — an absence of, or poor, mental health. Languishing is a counterpoint to how we might feel in prime mental health, full of wellbeing or Flourishing. While languishing may not be necessarily dangerous in itself, if you're languishing you may be at higher risk of mental illness. Some steps Adam suggests we can take: Naming our state can be a first step to doing something about it Looking for small wins that show us progress Asking how our friends and family are doing — having the opportunity to speak to someone about it You also might consider working on the 5 Ways to Wellbeing, getting in some forest bathing, walking a labyrinth, aiming for some flow, noticing when you're happy, or seeing what might bring you hope. — The term languishing for that part of the mental health continuum is from Corey Keyes. See for example, Corey L. M. Keyes. “The Mental Health Continuum: From Languishing to Flourishing in Life.”Journal of Health and Social Behavior, vol. 43, no. 2, 2002, pp. 207–222. Armchair and inspiration, as usual, from Bill Watterson. Order a printWWW…

Read more…